Pickle Passion: Embracing Food Sovereignty and Community through Canning

The air was ripe with excitement as attendees gathered at the Four Sisters Farmers Market in Minneapolis for the annual Pickle-Off. Organized by Cassie Holmes, a citizen of the Lac Courte Oreilles Lake Superior Band of Ojibwe, this event celebrated not just the art of pickling, but also the spirit of unity and food sovereignty within the Indigenous community.

The art of preserving food brings communities together.

The art of preserving food brings communities together.

A Tasty Competition with Purpose

The friendly competition began with jars popping open as participants eagerly dished out their culinary creations to be sampled and judged. Holmes, along with her fellow organizers, took pride in creating trophies and certificates adorned with the phrase “kind of a big dill,” a playful nod to the pride and joy of pickling enthusiasts.

The initiative at its core promotes food sovereignty—the belief that Indigenous people can and should reclaim control over their food sources and diets, cultivating local healthy food networks. Sponsored by both the Native American Community Development Institute and the Indian Health Board of Minneapolis, the Pickle-Off highlights these ideals while fostering community connection.

Every pickle tells a story; it began many years ago when an urban farmer at Little Earth of United Tribes proclaimed his pickles were the best. This playful challenge grew into a friendly rivalry with others, sparking a city-wide celebration of local flavors and skills. The event has since expanded to involve multiple entrants and categories, inviting anyone with a passion for pickling to join the festivities.

Building a Canning Community

Participants like Tyra Payer and Paige Hietpas, who run a budding canning business aptly named CanIHaveSome, expressed the joy found in their craft. Hietpas highlighted that, “At the end of the day, this is just a life-giving project for us.”

It’s clear that canning is about more than just preserving food; it’s a medium for expressing cultural heritage and keeping traditions alive. As Payer noted, it fosters a community spirit: “It’s a way to have fun. It’s a way to eat healthy delicious foods and share it with loved ones.”

Throngs of people enjoying the pickle-off competition.

The Judges’ Choices

This year’s contest saw entries judged on visual appeal, color, crunch, and, of course, taste. Destiny Jones, a Ho-Chunk citizen, clinched the “Best Pickle” trophy with her Spicy Dill recipe. Jones incorporated fresh herbs, garlic, and spicy peppers, a combination that certainly turned heads and tantalized taste buds.

Dr. Angie Erdrich, a pediatrician and Turtle Mountain Ojibwe citizen, also showcased her culinary skills, bagging the award for her delightful bread and butter pickles. Her secret? Growing her own cucumbers in an innovative vertical space, which is vital for urban gardening practices.

According to Jason Garcia, a judge and advocate for building local Indigenous food networks, the Pickle-Off encourages a reconnection with gardening.

“Taking care of their food and taking ownership of what they’re putting into their bodies. It’s really a full, holistic approach to food sovereignty.”

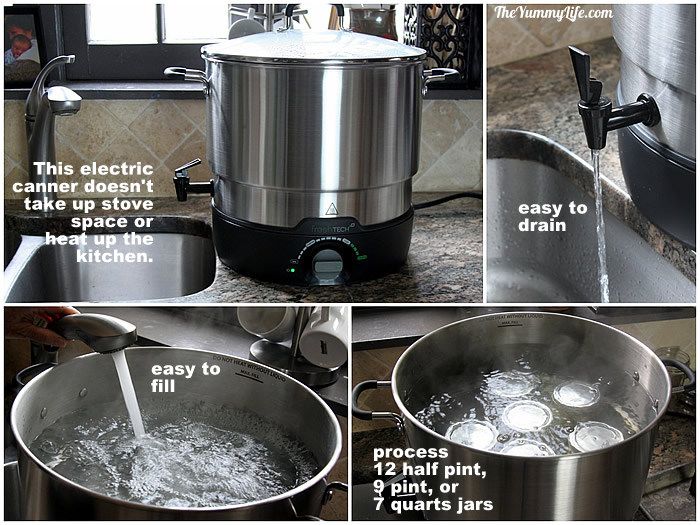

The Revival of Home Canning

The Pickle-Off now stands as a beacon of home canning’s resurgence, a trend that blossomed during the pandemic as more people sought to cultivate their gardens and preserve the fruits of their labor. As enthusiasts and newcomers alike dust off their canning equipment and dive back into the art of preserving, it evokes nostalgia among many—reminding them of days spent at their grandparents’ side, sweating over hot stoves.

Hands-on canning classes kickstarting a new generation’s culinary tradition.

Hands-on canning classes kickstarting a new generation’s culinary tradition.

As Morgan King notes from her own experience in Southeastern North Carolina, “While canning was once commonplace, it saw a decline after WWII. Today, it’s a hobby filled with communal sharing, where knowledge is just as valuable as the end product.”

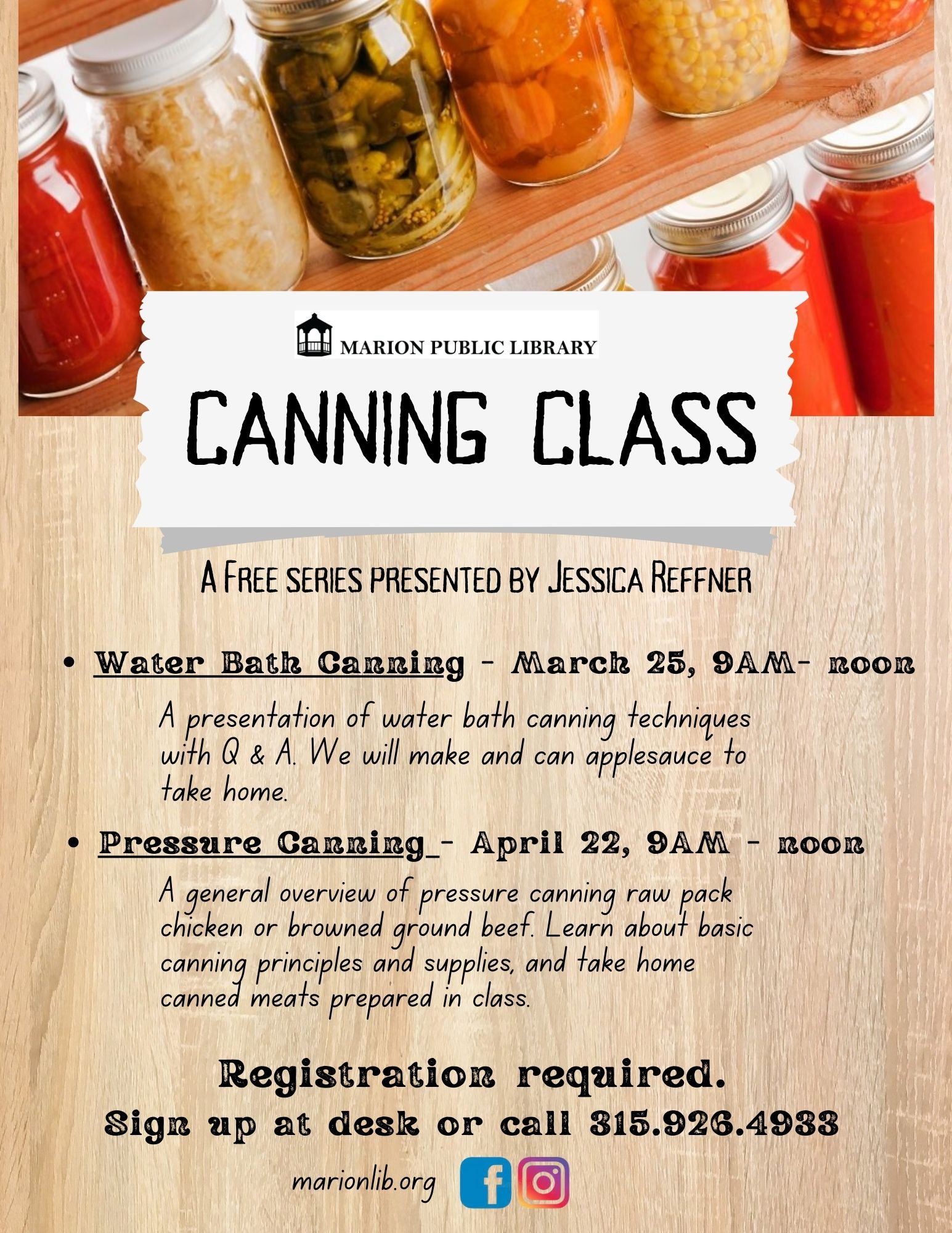

Learning the Craft Safely

With this uptick in interest comes the responsibility of food safety. Mistakes in canning—whether using untested recipes or neglecting pressure canner gauges—can have dire consequences, including foodborne illnesses. Ensuring safe practices is paramount.

If you’re eager to start canning at home or simply want to refine your skills, consider signing up for classes—like the upcoming one on October 7, led by Avery Ashley, the Family & Consumer Sciences Agent from the Brunswick County Cooperative Extension. Participants will enjoy hands-on instruction while canning dill pickles.

Conclusion: A Celebration of Food, Culture, and Community

Ultimately, the Pickle-Off showcases a powerful blend of food, culture, and community engagement. It stands as a vibrant platform for sharing knowledge, celebrating creativity, and reclaiming food practices that highlight Indigenous heritage. So, whether you’re a seasoned canner or a curious novice, remember: every jar of pickles tells a story, each bite a connection to your community and beyond.

For those interested, don’t forget to register for the upcoming canning class. It’s a delightful opportunity to deepen your knowledge and relish in the joy of food preservation.